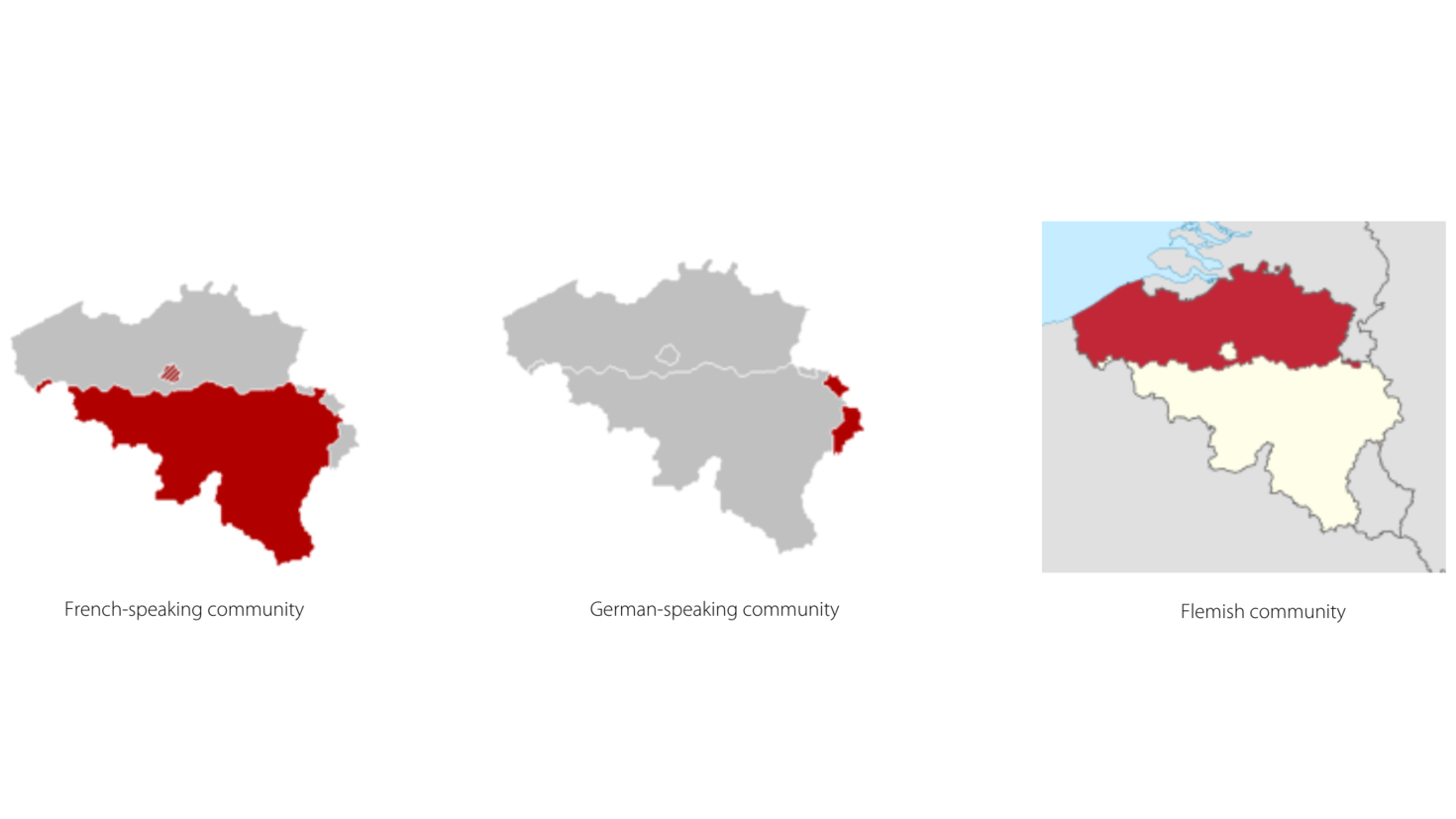

Belgium's constitution recognizes three linguistic communities: the Dutch-speaking Flemish, the French-speaking Francophones (including the Walloons), and the German-speaking Germanophones. Dutch speakers account for 55.7% of the population, Francophones for 31.7%, Germanophones for 0.3%, and allophones for 12.2%.

Aside from the massive use of Dutch (in Dutch: Nederlands), which is a Germanic language as English is, "Nederlandophones" speak dialects such as Flemish (Vlaams), Brabants (Brabants) and Limburgish (Limburgs), all derived from Dutch. Virtually all Flemish citizens speak their dialect at home or with friends, while keeping Dutch itself (the cultural language) for more formal exchanges. This combination of dialect and Dutch isn't haphazard or accidental: it stems from a number of unwritten conventions spawned from Flemish culture and tradition.

In short, Dutch dialects in Flanders have remained very active, but are losing pace in the Netherlands (except possibly for Limburgish and Saxon). The term Flemish (in English) or Vlaams (in Dutch) refers to the dialect, not to the Dutch language per se (Nederlands). That's why the Flemish people object to the word Vlaams being used to designate Dutch proper. The differences between Dutch spoken in Flanders and that spoken in the Netherlands are tiny, but they can be detected in pronunciation and vocabulary. The Flemish live essentially in Flanders and in Brussels; those in Wallonia are not accounted for.

Wallonia's Francophone citizens generally speak French as a mother tongue or first language, but in the province of Hainaut, some also speak Picard or Walloon; the latter, which is spoken by anywhere from 15 to 30% of Walloons, is still used in the provinces of Luxembourg, Namur and Liège, but also to the east of Hainaut and throughout Walloon Brabant. Citizens also speak Rouchi (a Picard dialect) to the west of Hainaut; Champenois, in a few Namur and Luxembourg communes; and Gaumais (Lorraine dialect) south of Luxembourg province. Like French, all of these dialects (which linguists call languages) derive from Latin. Today, no one speaks onlythese "languages," which are deemed compulsory with friends and family, but give way to French in formal communication. Note that Belgian Francophones live in Wallonia and in the Brussels-Capital Region (BCR).

Germanophones make up Belgium's third linguistic group, with over 70,000 regular speakers in the region located in the province of Liège (to the east). In addition to standard German, Germanophones speak Moselle- Franconian and Low-Franconian dialects. However, these dialects are constantly losing ground and are handed down less and less-and not at all anymore in some cases-from generation to generation. They appear to be on the road to extinction.

In addition, Belgium has four linguistic regions : French-language in the south; Dutch-language in the north; German-language in the east; and the bilingual region (French-Dutch) of Brussels in the centre.

Unlike Belgium's provinces, Canada's are not organized by law into linguistic regions. At most, Canada's provinces have bilingual municipalities whose linguistic status is set either by a provincial law or by a municipal by-law.