By Mohamad Chahrour and Baher Migally

Special Guest Writers

Mohamad Chahrour and Baher Migally are 4th year Faculty of Medicine students in the Honours Bachelor of Science Program in Translational and Molecular Medicine. They wrote this story originally for their Science Communications course as part of a series profiling researchers at the Faculty of Medicine.

The course is designed and taught by Dr. Kristin Baetz, director of the Ottawa Institute of Systems Biology and professor in the Department of Biochemistry, Microbiology and Immunology, to foster in students the ability to convey complex science to a lay audience – an essential skill when making presentations, applying for grants, composing abstracts for research papers and generally communicating one’s work in the biomedical sciences.

MedPoint will be publishing profiles from this series throughout 2019 .

___________________________________________________________________________________

You sit at the dinner table, staring at your plate. Your spouse has tried to cook. You force your facial muscles not to flinch as you take the first bite…. It’s not awful—but it’s far too bland. You sprinkle a dash of salt on the dish and it makes a world of difference. “It’s good, honey!” you say, thanking God for salt—such an amazing tool.

Recently, Dr. Jean-Simon Diallo, an assistant professor in the Department of Biochemistry, Microbiology and Immunology and a researcher at the Ottawa Hospital Research Institute (OHRI), has basically invented the figurative ‘salt’ of one particular type of cancer treatment—meaning potentially better results for patients.

A bit of background:

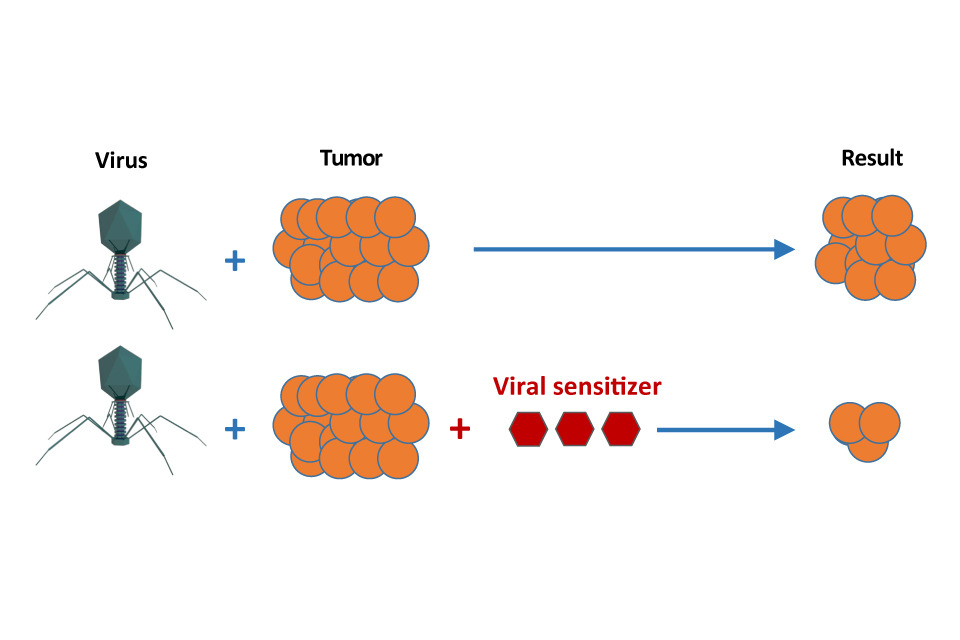

Cancer occurs when some of the body’s own cells begin dividing excessively. The immune system doesn’t fight hard against these cells because they’re recognized as being part of the body—thus the necessity of cancer treatment. Many cancer treatments focus on targeting rapidly dividing cells, while leaving regular cells alone. “Oncolytic virotherapy” is a term used to describe the use of viruses engineered for this purpose. Viruses work sort of like pirates: they infect cells and hijack their machinery to make more viruses. Eventually, when enough new viruses accumulate in the cell, it bursts and dies, releasing more viruses, and the process repeats itself. The idea is to use viruses that infect only cancerous cells, and simply let the viruses work their magic. Ironically, a problem arises because of the immune system, which recognizes the viruses as foreign and fights them—and therefore oncolytic virotherapy doesn’t always work efficiently.

Back to Diallo’s salt.

“My research focuses on identifying ways to improve the capacity of viruses to infect tumors. The approach we've chosen is to use small molecules that can be administered at the same time as a virus, to help the virus get into those tumors and replicate inside them,” says Diallo. Essentially, like bland food, the viruses on their own leave something to be desired. Add some of these small molecules, which Diallo calls “viral sensitizers,” and much like adding salt, things go a lot better and viruses are able to infect cancerous cells much more efficiently. In terms of using viruses to kill cancer cells, this is great news.

Admittedly, it’s not quite as simple as adding salt.

In reality, those viral sensitizers are hard to come by, and—even when they’re found—there are issues: either the molecule is not well tolerated by our bodies as a drug, or we don’t actually know how the molecule functions, so we can’t use it.

A decade after the initial discovery of viral sensitizers, in what Diallo calls the “Aha!” moment, a scientific paper was recently published describing the mechanism of action of dimethyl fumarate (DMF), a molecule known by Diallo’s lab to function as a viral sensitizer. It just so happened that DMF is also an approved drug for treating multiple sclerosis and psoriasis (that is, it is well tolerated). And just like that, everything fell into place: DMF is a viral sensitizer, its mechanism of action is known, and it’s already an approved drug.

The “salt” of oncolytic virotherapy was born.

While his lab has had tremendous success in animals, the next step for Diallo is to actually get the viral sensitizers into clinical trials—a task that takes an incredible amount of work and funding. But as Diallo says, “It’s an exciting time to be working in the realm of oncolytic viruses, because investments into it are increasing at a tremendous pace.” He goes on to say: “There's lots of promise, and let's hope that the hype lives to fulfill that promise.”

Let’s hope together that cancer treatment can truly become as simple as adding salt to your food!

Main photo credit: Yanalya, Freepik