By Chonglu Huang

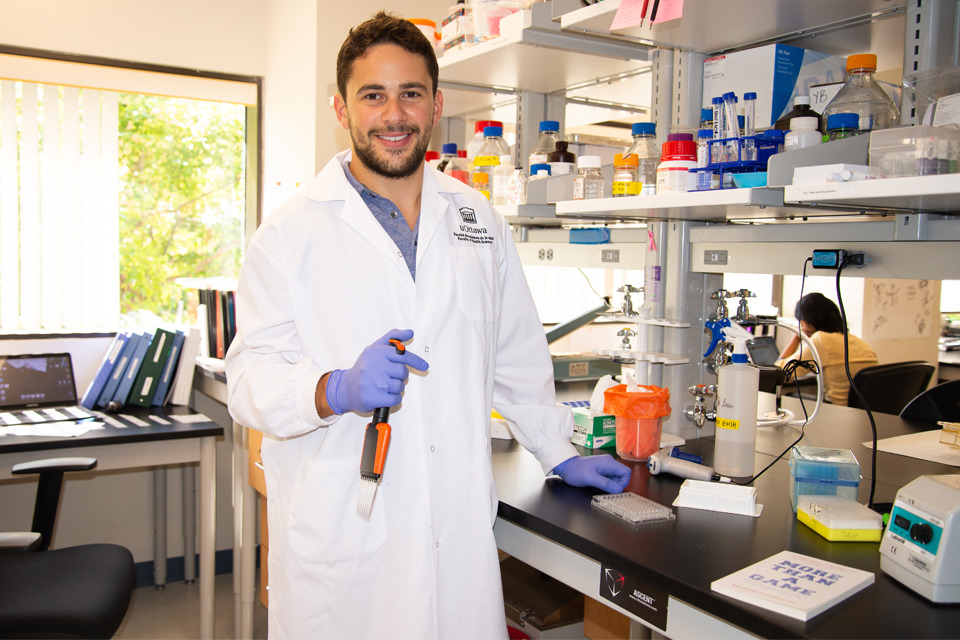

University of Ottawa MD student Nathan Chiarlitti has an incredible passion for medicine, but it was his perseverance and eternal optimism that earned him an acceptance to medical school on his third round of applications.

“It was humbling to receive those rejection letters from a dozen or so medical schools the first two times I applied,” says Chiarlitti, who has a Bachelor of Science in Human Kinetics from St. Francis Xavier University and a Master of Science in Exercise Physiology from McGill University.

“At the same time, I was confident that if I didn’t get accepted on my third try, I would still apply again.”

As a long-time athlete who spent over two decades playing hockey for junior leagues, university leagues and Team Canada, Chiarlitti says he owes his work ethic and positive attitude to the game of hockey.

Wanting to inspire others, Chiarlitti wrote and self-published his first book, More Than a Game, which shares his journey and argues that the sport allows players to develop important qualities applicable to their everyday lives.

“Lessons from the game of hockey transcend arena walls,” Chiarlitti describes. “I see every day, when I’m interacting with colleagues, professors, doctors and patients, how similar challenges in medicine are to challenges on the ice with teammates and coaches.”

Now in his second year of studies, Chiarlitti shares the top five qualities that he learned from his journey as an athlete and an academic.

1. Persevere: “I told myself, give yourself the chance to try again.”

As a child, Chiarlitti’s career goal was always to be a professional hockey player, but midway through his junior hockey career in the OHL, his prospects were falling short.

In his first two years of eligibility, he wasn’t drafted, or selected for an NHL tryout. Finally, after his last major junior season, he was invited to an NHL camp with the Arizona Coyotes.

While he never played in the NHL, he was becoming more and more curious about medicine.

“I had a lot of experience with doctors throughout my athletic career because of various injuries,” says Chiarlitti. “I always saw them around the rink and I remember casually talking to them and it seemed really interesting.”

Chiarlitti applied the same perseverance to his pursuit of professional hockey as he did to medical school applications. When he didn’t get accepted to any school the first two times he applied, he worked harder and persevered.

“I drew a lot of comparisons to my hockey experience—to give myself the chance to try again,” he says.

2. Have a strong work ethic: “I realize that I need to work harder when the stakes are higher.”

Reflecting on his minor hockey career, Chiarlitti says he was a good player, but he learned quickly that if he wanted to excel from minor leagues to major junior and varsity teams, he needed to work harder.

It was the same for medicine.

“When I applied to medical school the first time, I thought I was a well-rounded applicant with good grades, a high GPA, a varsity athlete, and I didn’t even get an interview offer,” says Chiarlitti.

“It was a humbling experience. I thought I was at the top, but I had to raise my level of competitiveness to another notch. I was confident I would put in the work and apply again.”

3. Be positive: “Whether things are good or bad, you have to be the same person.”

Chiarlitti says that one of the biggest things that sports gave him was a positive attitude.

“With hockey came leadership, comradery and teamwork. If things didn’t go well for me, I still had to be the same leader and teammate in the dressing room and on the ice,” he explains.

“I was the captain of a hockey team. If I let my emotions and the challenges I was facing affect my day-to-day behaviour, then other people would notice and it wouldn’t be the best for the team.”

4. Make sacrifices: “I wasn’t dreading the sacrifices because I had hopes that it would pay off.”

Chiarlitti says his desire to be in medical school gave him the motivation to balance both varsity hockey and his academics in university, allowing him to put forward a competitive application.

“Sacrifice for me means that when you want something bad enough, you’d put in the work to achieve it,” he says.

Chiarlitti learned the value of sacrifice at a young age through playing hockey. Often, he would train twice a day in the summer, be the first at optional skates, and get extra coaching to give himself the edge.

“While other people my age were out drinking, partying and travelling, I had to rein it in,” he says. “Often, I couldn’t go out because I had to train.”

Chiarlitti says it never felt like a sacrifice to him because he was excited to put in the work doing something that he loved—whether that was playing hockey or studying for medical school.

5. Be grateful for your own timing: “Everything happens to a reason.”

Chiarlitti says he feels a deeper sense of appreciation for being in medical school today than he would have, if he had been accepted the first time.

“I feel more mature and I understand the gravitas of it in a different way than I did when I first applied at age 23,” he explains. He also draws parallels to his hockey journey when he realized that it was a blessing in disguise that he wasn’t drafted to an NHL team or selected for an NHL tryout when he was 18.

“I was happy that they invited me at age 21 when I was smarter, stronger, more mature and more mentally tough to handle an NHL camp,” says Chiarlitti, who adds that this message of being grateful in the moment is also one of the reasons why he wrote his book.

“I felt like it was an important message to share,” he says. “Competitive hockey in Canada has become so focused on outcome goals: the end result of playing professionally and making a lifestyle out of the game. In reality, so few make it to the NHL. The focus of the game shouldn’t be solely on how to play pro, but how to make the player a better person.”

Many challenges that Chiarlitti faced in hockey, he has also seen in the medical profession and the skills in leading, mediating and working together are universally applicable.

Earlier this spring, Nathan Chiarlitti was interviewed on CTV Ottawa and the web show #StreetChat about his personal experience as a hockey player and a medical student. More Than a Game is his first book.