Fedor Bohatirchuk could have been a professional chess player in the Soviet Union.

Instead, he dedicated his life to medicine, a choice that eventually brought him to the University of Ottawa — after many twists and turns of fate.

A Zhivago-like figure

The son of a violinist and a choir conductor, Bohatirchuk was born in 1892 in the Ukrainian city of Kiev, which at that time belonged to the Russian Empire. He began playing chess as a teenager, and continued throughout his medical studies at the University of Kiev.

He served in the Russian military’s medical corps during the First World War, and worked in a military hospital during the subsequent Bolshevik Revolution and Russian Civil War, which raged until 1922. Some writers have claimed that Bohatirchuk inspired Boris Pasternak’s famous character Dr. Zhivago, a military physician in early 20th century Russia who becomes disillusioned by Communist totalitarianism and propaganda.

Choosing science over chess

In the 1920s and 30s, he specialized in the emerging field of radiology, conducting cancer research while working as a teacher and clinician. He rose in the ranks of chess, competing in six Soviet championships between 1923 and 1934. However, he refused to dedicate himself full-time to the pursuit, since he considered his medical and scientific work more important. His refusal displeased the Soviet government, which saw chess as a tool of propaganda: brilliant chess masters, like top athletes, would demonstrate the superiority of the Soviet state. In 1937, he was summoned to the Department of Propaganda of the Communist party to explain himself.

“The head of the department read me a lecture about the significance which the party and the government attach to chess for the cultural development of the young and told me that my abstentions had produced a very bad impression,” he later wrote. “When one recalls that 1937 was the year of the beginning of mass persecutions and purges … I saw that I had to give up chess; my infrequent appearances at chess tournaments only irritated my adversaries and furnished material for my enemies to use against me.”

War veteran and refugee

When war once again broke out in 1939, Bohatirchuk served as the head of the Ukrainian Red Cross. While compassionate toward Russian prisoners in German POW camps, he was outspoken in his opposition to Stalin and the Communist party. The Soviets removed many of his games from their official records as a result of his perceived treason, but some were later reclaimed by chess historians, using outside sources.

In 1944 he joined the Committee for the Liberation of the Peoples of Russia, an East European militia also known as “Vaslov’s Army” that fought with the German Wehrmacht against the Communist Red Army. Though considered by some as a collaborationist force, Vaslov’s Army explicitly rejected the Nazi’s anti-Jewish ideology, and later turned against the Nazis to help Czech forces liberate Prague. Bohatirchuk later wrote: “It was a tragedy of history that I and thousands of others who flew West during the war years were obliged to run away to one desperado to avoid another. God and our conscience remain our only guides.”

As the Russian Army marched westward in the dying days of the war, Bohatirchuk fled for his life, finding refuge in a displaced persons camp in the American-occupied zone of Germany. Chess lore has it that, while in the camp, he played chess under the pseudonym “Bogenko” to avoid being identified as a Russian national and repatriated to the USSR.

In 1948, Bohatirchuk emigrated to Canada to join University of Ottawa’s fledgling Faculty of Medicine. Father Lorenzo Danis, who led efforts to open the medical school, travelled to war-torn Europe to recruit high-caliber scientists such as Bohatirchuk. (see the article “The founding of the faculty.” )

“Our teachers that came from Europe were under some stress,” recalled MEDS ’54 alumna Doris Kavanagh Gray recently. “We were respectful of them. We knew that they were knowledgeable people, but we felt kind of sorry that they had to be disrupted the way they were.”

A distinguished scientist

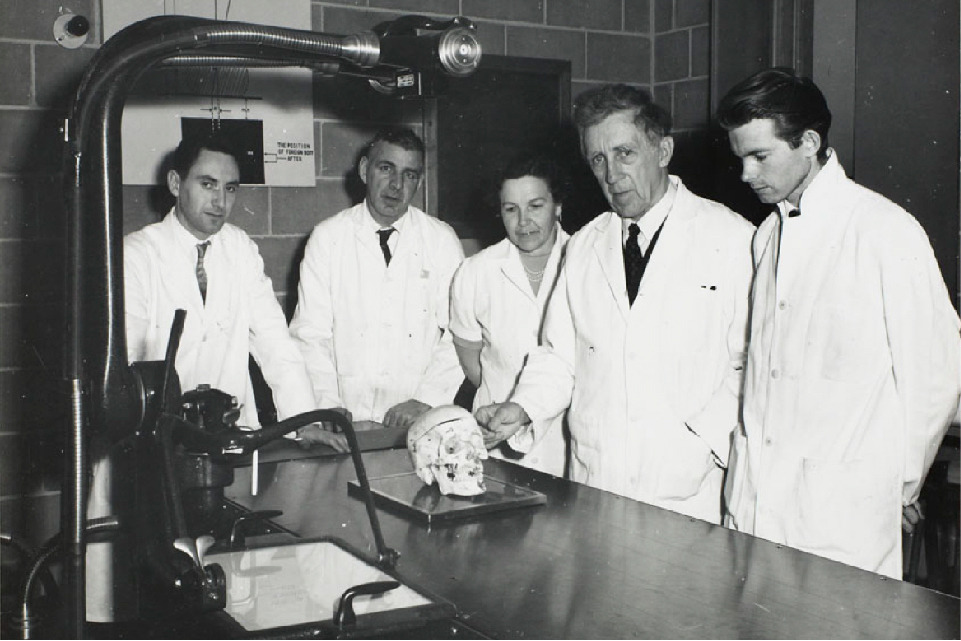

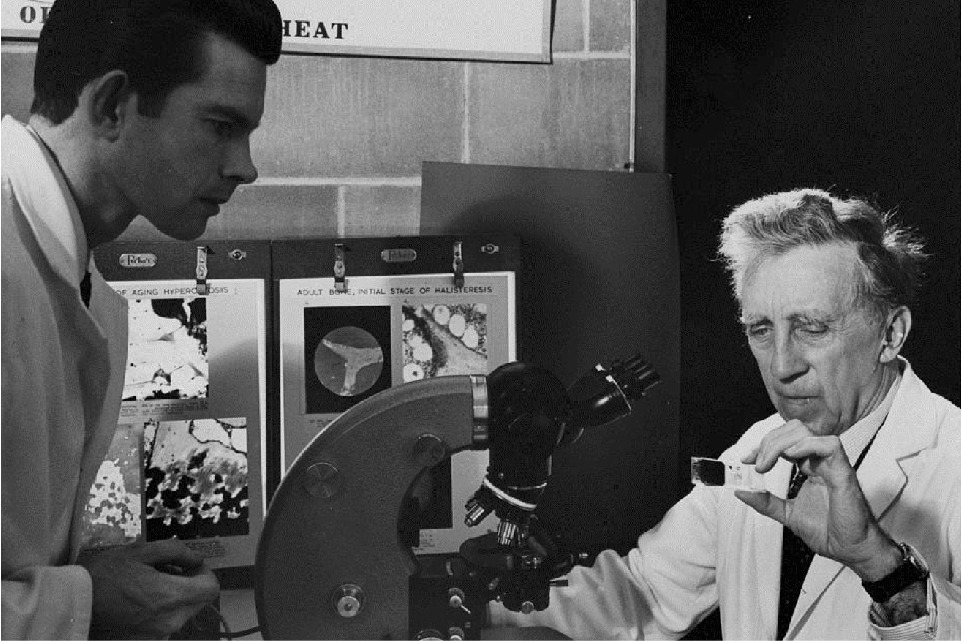

He was hired as a professor in the anatomy department in 1949, where he worked as a teacher and researcher until his retirement in 1970 at the age of 78. His many articles, on topics such as microradiography and clinical applications of radiography, were published in academic journals including the British Journal of Radiography. In 1955, he was awarded the Barclay medal by the British Institute of Radiology. His Barclay Prize essay “The Ageing Vertebral Column (Macro- and Historadiographical Study)” (pdf, 4,445.27 KB) was printed in the British Journal of Radiology in August, 1955.

Bohatirchuk continued playing chess and represented Canada at the Chess Olympiad in 1954 in Amsterdam. Although Canada applied to the International Chess Federation to award Bohatirchuk the title of International Grandmaster, the Soviet Chess Federation vetoed the motion because they saw him as an enemy of the State. He was instead granted the title of International Master.

Throughout his life, Bohatirchuk remained active in politics as part of the Canadian Ukrainian community.

He died in 1984 at age 91, and is buried in Pinecrest Cemetery in Ottawa.

.