By Laura Darche

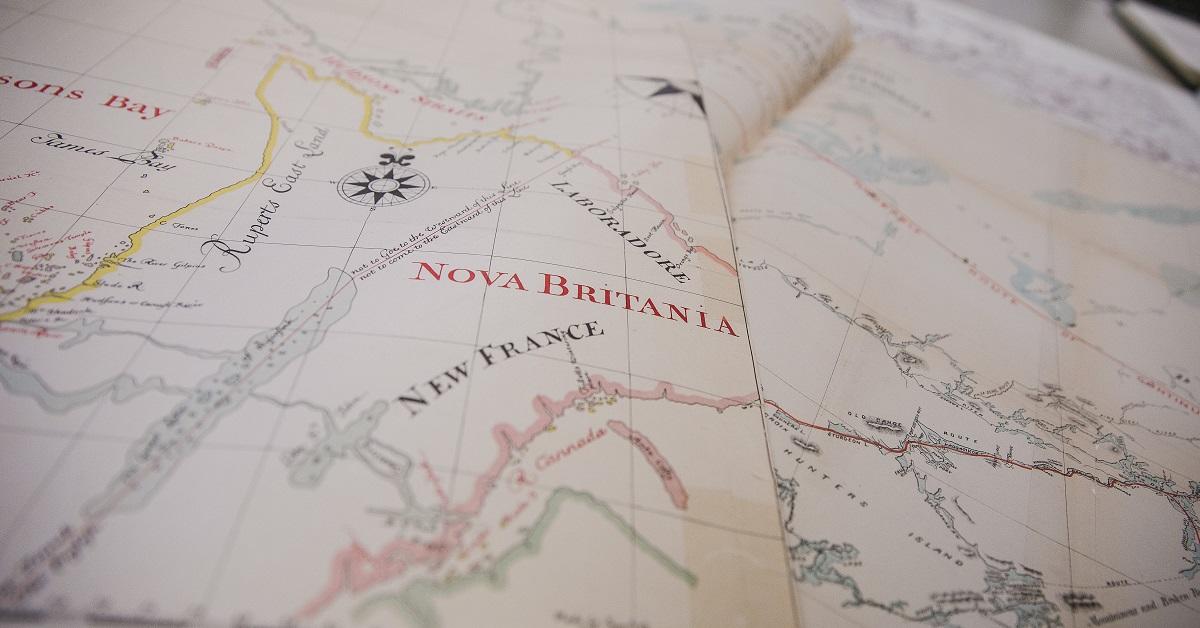

Languages can be protected in many ways, including through an original method devised by France Martineau: a space-time map of French-speaking North America that shows which factors do, or do not, pose a threat to the vitality of French and of languages in general. To build this map, Martineau crisscrossed the continent to meet with members of French-speaking communities, pore through their archives and hunt down information that allowed her to overturn preconceived ideas about language.

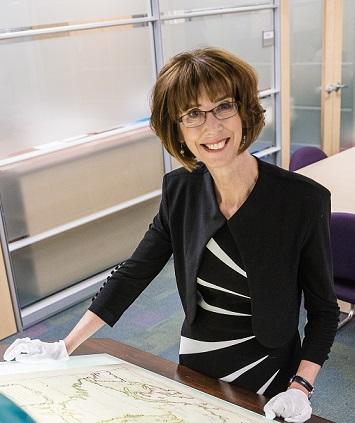

An Outaouais native, France Martineau is a distinguished professor in the Département de français who holds the Research Chair in Borders, Networks and Contacts in French America. As a founding director of the Polyphonies du français laboratory, she has dedicated her career to studying the evolution of French. In November 2018, she was awarded the Ordre des francophones d'Amérique in honour of her contributions to maintaining and promoting the vitality of the French language in North America.

Here are a few of her findings:

Anglicisms will lead to the demise of French: FALSE

When two communities live in the same area, they naturally influence each other. They share ideas, recipes and vocabulary. However, borrowed words do not turn one language into another: during the Middle Ages, English borrowed half of its vocabulary from French without turning into French. Martineau has also discovered that when words borrowed by Francophones are incorporated into the French language system, French words with the same meaning as the borrowed words do not disappear; instead, they are repurposed to perform a new function. For example, when “so” (in English), is used in French to mean alors or donc, it does not replace these two French words and its use is restricted to informal speech. Hence, this borrowing enriches the language by giving its speakers an expanded range of expressions. Far from a flaw, this normal ability of language to incorporate outside elements is a sign of its vitality.

“After comparing communities that have greater contact with English to those with less contact, we see relatively few differences in structures, only in borrowings from vocabulary.”

French-language institutions serve no purpose: FALSE

The greatest threat to the survival of a language occurs when speakers decide to stop speaking it and newcomers refuse to learn it. After studying the evolution of French in different settings (minority, majority, officially recognized or spoken only at home), Martineau was able to observe the impact that the status, or change in status, of a language can have on these decisions. Minority status and non-official status seriously increase the vulnerability of a language because its absence from the public domain causes an entire swath of the language to disappear: the more formal levels fall into disuse, leaving behind only the familiar level of language. Over time, these limitations can lead communities to abandon their language as one generation follows another. In this regard, institutions have an important role to play in preserving a language.

“The more opportunities we make for a language to extend to different registers, the greater our assurance that it will remain vibrant.”

French from France is better than French from Canada: FALSE

A common mistake when comparing European French to North American French is to compare popular French used in Canada to formal language used in Europe. Everyone knows that people speak differently among friends than in an interview. So why do grammar books often characterize Canadianisms as informal language? It creates the impression that French-speaking Canadians have no formal level of language. According to Martineau, who compared language variations, the actual differences are not so pronounced. She is working on the first book about the history of grammar in North American French, which describes various language registers, explains the origins of our expressions and maps the Francophone populations that share such expressions.

“The threat is not contact, it’s the way the speaker perceives his or her own language and identity. If we constantly insist that the French used in Canada is far inferior to that used in France, we end up with people afraid to speak it or uninterested in learning it.”

Multiculturalism is eroding our identity: FALSE

Bilingualism is the simplest form of multiculturalism and can be found almost everywhere on the continent. Hailing from all over the world, immigrants to North America adopted French, English or both when they arrived in Canada, thus contributing to our rich heritage. This natural intermingling of populations has create multiple identities, especially in large cities. Martineau noted that young Francophones in the suburbs of Paris essentially ask themselves the same questions about language and identity as young Montrealers. She contends that despite these more complex identities, young people truly feel rooted in the community that lives in their memory.

“Rather than being a barrier, language is a vehicle for reaching out to the other. The history of French in North America isn’t linear; it’s complex and multifaceted, open to others and enriched by the arrival of every new population.”

More about the work of France Martineau

Since 2005, France Martineau has been awarded two major grants from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council under the Major Collaborative Research Initiatives program. The first concerns the history of French from its medieval origins to the Renaissance, and the second, ending in February 2019, centres on French in North America (Le français à la mesure d’un continent : un patrimoine en partage).

Thanks to the second grant’s funding, she spent three summers crisscrossing the continent in a Westfalia camper van, from east to west and north to south, visiting Francophone communities and their archives. Over the past 20 years, she has amassed some 25,000 letters. This correspondence between members of the same family spans several generations, allowing her to track the evolution of the communities where these people lived.

In addition, Corpus FRAN, a collection of interviews by France Martineau and her collaborators conducted in 20 Francophone communities, attests to the variable status of French in North America today.

Moreover, the nineteenth title in Les voies du français, Martineau’s collection of works on French-speaking North America, was recently published by the Presses de l’Université Laval (Francophonies nord-américaines : langues, frontières et idéologies, under the editorial direction of France Martineau et al.).